Recovery-based approaches to mental health | November 2024 – May 2025

The Context

In recent years, recovery-based approaches to mental health have reshaped the model of mental health care. The focus has shifted from a rehabilitative or medical model, which centres on the professional, to a recovery model that prioritises the person experiencing mental distress.

The recovery model is defined as ‘a way of living a satisfying life, full of hope and contribution, even within the limitations caused by the disease’. In this context, person‐centred care became the focus of the intervention. However, there are some problems associated with applying this model. For example, some feel it oversimplifies the issues connected to mental distress. Furthermore, there is a lack of a shared definition and understanding of the model, which makes evaluation difficult. IMPACT has selected recovery-based approaches to mental health as an important issue to consider, in order to improve the lives of people with mental health distress and their carers.

What does the Existing evidence say?

Although there is no univocal definition of recovery, there is consensus that recovery does not necessarily imply only the “cure“. However, evidence noted that health professionals, and often people using mental health services, are not aware of the distinction between recovering (the process) and recovery/recovered (the outcome). There are two main meanings of the term “recovery” in mental health systems internationally:

- The biomedical or traditional model aims for clinical (or scientific) recovery. In other words, it seeks recovery from mental illness.

- The recovery-based approach to mental health aims for personal or social recovery, meaning recovery with a mental illness.

The recovery-based approach stemmed from various civil rights movements, starting in the 1960s, as a response to stigma and suppression in the psychiatric system. These movements are based on ideas of human rights and empowerment. The term “recovery,” as it is used by the recovery-based approach, first appeared in the 1980s through the consumer/survivor movement.

The central idea of the recovery revolution was that mental illness is only one element in a person’s life. For this reason, recovery cannot be reduced to the “cure” of symptoms. It must encompass the illness, while pursuing a full and meaningful life despite its challenges.

Recovery models help to challenge negative attitudes and assumptions that people living with severe mental health conditions can only get worse.

Evidence Review

The evidence review highlighted that a recovery-based approach has positive implications both for people using services and practitioners (Martinelli and Ruggeri, 2020).

- Better outcomes for people with mental distress;

- Reduction of health costs;

- Greater value on the personal knowledge of the individual and balance in the power which historically was held by psychiatrists and professionals in the mental health care service;

- A better focus on the personal priorities of the person using the services rather than on what is defined by the professionals.

Evidence also highlighted the main barriers to the implementation of recovery-based approaches:

Across the Four UK Nations

In England, personal recovery is strongly advocated within mental health service policies, such as No Health without Mental Health and the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health. However, evidence highlights a strong contradiction between the dominant medical model and the shift to a recovery approach in England.

In Wales, the Mental Health (Wales) Measure 2010 led to a restructuring of mental health services. Evidence recognises that the new service structure is underpinned by recovery principles, as it promotes self-management, independence, and co-production.

Scotland was the first of the UK nations to adopt recovery-based approaches to mental health. Recovery principles were introduced into Scottish mental health policies, with the Scottish Recovery Network playing an essential role in making this happen.

In Northern Ireland, the Bamford Review in 2007 led to significant improvements in care for people with mental health problems. As a result, more attention was given to recovery, alongside the development of assessment criteria. While Recovery Colleges have embedded a recovery-oriented practice in mental health services, research findings highlighted that the medical model still dominates in Northern Ireland.

Networks are meeting across the UK, coordinated by:

In England:

MIND (North Kent)Changes Plus

Rethink Mental Illness

Community Glue CIC

In Scotland:

Penumbra

In Northern Ireland:

Laura Doyle

When discussing the existing evidence on recovery-based approaches, network members said:

- The contrast between recovery-based and medical approaches is too simplistic. Recovery in mental health should not be reduced to a binary choice. Instead, the two models can work together.

- Recovery holds different meanings, and these meanings can change for the same person throughout their life. “Everyone is different; there is no ‘set in stone’ way to deal with people as we have our own journeys.”

- Recovery is closely connected to community life. Therefore, raising awareness and educating people about mental illness should be part of recovery support.

- Evidence tends to focus heavily on the medical aspects of mental illness. However, everyone could experience mental health challenges at some point, which may not require medical attention but rather community support.

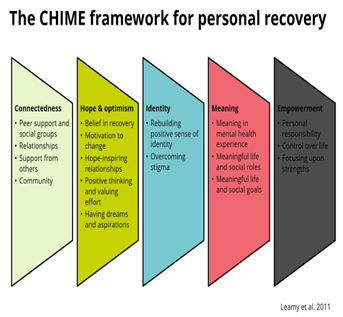

Networks recognised the CHIME Framework (Image from The Recovery Place website) as a good framework because:

“Empowerment really stands out to me”

“I can relate to the part about meaning – I care about the meaning I find in my life and what I’m involved in”

“It emphasises the importance of the social network”

The following models were identified as good practices:

When looking into the implementation of recovery-based approaches, network members highlighted some systemic challenges:

- Limited resources and funding compromise the proper implementation of recovery models. A key question is how to sustain mental health recovery with short-term projects and interventions.

- Some challenges are linked to applying the model according to diagnosis. For example, when people lack awareness of their condition’s severity or are in an acute state of addiction, the recovery model may not fit. Participants also noted that recovery is not tied to diagnosis. One network compared it to diabetes: “You don’t recover from diabetes but you can live well with it.”

- Stigma and language continue to create barriers to accessing recovery-based services. People remain afraid of being labelled as having a mental illness. Therefore, members suggested using the term “well-being,” which feels more acceptable.

- Community services and peer support often lack sufficient funding.

- Co-production must go beyond consultation. If services are led solely by statutory bodies and professionals, power imbalances remain, undermining the empowering purpose of co-production.

- Involvement of people with lived experience in Integrated Care Board (ICB) commissioning remains too limited. When statutory services dominate decision-making, power imbalances are particularly strong.